September 26, 2022

Amman-Baghdad-Cairo (ABC) Agreement: A new path for economic integration

Table of contents

Executive summary

The ABC Agreement from Egypt’s perspective

The ABC Agreement from Iraq’s perspective

The ABC Agreement from Jordan’s perspective

Executive summary

Overview

Since 2019, Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan have held multiple summit meetings to discuss trilateral agreements to formalize and deepen economic integration. Throughout this report, this effort will be referred to as the Amman-Baghdad-Cairo (ABC) Agreement. By cooperating among themselves, the three countries can represent a united political and economic front and a collective 150 million citizens, with more than $500 billion in gross domestic product (GDP) and access to major trade routes, markets, and economic and political relationships.

However, the Middle East has a history of optimistic proclamations and agreements that are announced with great fanfare and eventually amount to little1 See Appendix I. The key factor that will determine the success of the ABC Agreement is whether it can bring tangible, practical benefits to the three participating countries.

All three countries face significant economic, political, social, and environmental challenges. By cooperating on projects and linking their markets and policies, they are laying the foundation for potential gains from a stronger combined voice, economies of scale, and scope for specialization. However, this potential will only be realized if the final agreement is not just another optimistic proclamation but instead enacts detailed and specific measures to remove barriers and encourage cross-border cooperation and integration.

This report explores the potential benefits and pitfalls to avoid from the perspective of each country: Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq.

To do so, the Atlantic Council’s empowerME Initiative, in collaboration with the Iraq Initiative, invited three independent co-authors with expertise on Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan, respectively, to each write a country-focused chapter. Each chapter evaluates the potential and challenges of the ABC agreement from the point of view of each of the three countries. The evaluation focuses on economic and social gains and losses, excluding the debate on the political merits of, and motivation behind, the agreement.

By considering each country’s position independently, we have been able to highlight the potential benefits of the agreement for each country more pragmatically. It is worth noting that no agreement has been signed to date; instead, there have been multiple meetings between the three leaders to discuss the potential for initiating an economic cooperation framework.

This report will hopefully enlighten the discussion further, initiating a pathway for extensive research on the subject both within and outside the Atlantic Council.

Leveraging comparative economic strengths and weaknesses

For the ABC Agreement to succeed, each country must leverage its comparative strengths to address deficits in the other country/countries. The table below summarizes each country’s main challenges and opportunities pertaining to the ABC Agreement. In the report chapters, each element is explored in greater detail.

Egypt

Challenge

- Net importer of oil/low energy security

- Needs large amounts of imported fertilizer and other agricultural chemicals to meet its energy and food security needs

- Needs strong regional and international support in its water dispute with Ethiopia regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD)

- Turkey, Iran, and Israel have increased their economic and political penetration and relationships in the Arab world (such as Turkey’s intervention in the Libyan civil war), in some cases encroaching on what Egypt has traditionally viewed as its sphere of influence

Opportunity

- Could secure a stable supply of oil at a concessional price

- A land route could link Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq and carry a steady supply of oil from Iraq, and fertilizer and other agricultural chemicals from Jordan

- Regional leader in construction, financial services, renewable energy, and educational services; could increase professional and business services exports and knowledge in these areas to Jordan and Iraq

- Could support Iraq in developing its tourism sector through private-sector joint investment projects, particularly in the region of the Iraqi marshes and the ancient city of Ur

Iraq

Challenge

- Lack of economic diversification and reliance on oil rent

- Poor food security, underdeveloped agriculture sector, and deficient food-processing industry

- Poor water-resources management capabilities

- Poor energy security, with frequent power cuts in the hot summer season

- Poor physical infrastructure and urgent housing needs

- High unemployment, particularly among the youth

Opportunity

- Iraqi crude-oil production (as a primary energy source) significantly exceeds domestic consumption; a large quantity of about 4 million barrels/day can be exported; and Jordan and Egypt could supply joint refineries and petrochemical projects

- Could benefit from Egyptian expertise in the construction sector

- Reconstruction and marketing of historical/archaeological sites with support from Egypt and Jordan could eventually revive the tourism industry

- Connection to the two other nations’ electrical grids could address some of Iraq’s electricity needs

- Jordan could help develop Iraq’s water-resource management capabilities

Jordan

Challenge

- Lack of export market diversification in Europe, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa; Egypt could be route for improvement

- Decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) and local investment

- Start-ups don’t develop beyond early stage investment

- High unemployment, especially among women and the highly skilled

- Low energy security; has agreed with Iraq to build gas and crude oil pipelines from Iraq’s Basra to Jordan’s Aqaba, and Iraq has discussed extending it to Egypt

Opportunity

- Specialization in exporting vegetables, food products, minerals, chemicals, and textiles—items that Egypt and Iraq need

- Expertise in automating/digitalizing government services (e-government) is needed in Egypt and Iraq

- Health-tourism strength could be attractive to Egypt and Iraq

- Tourism knowledge could support Iraqi development of this sector

- Good knowledge acquired through and experience with Germany in water-resource management could be shared with Iraq

- Vast experiences with energy efficiency, household solar-energy devices, and methods of demand-side management in the power sector could help Iraq

High priority projects to pursue

Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq should consider the following projects as ways to quickly deepen cooperation and provide benefits to all sides:

- Oil sector: Establish joint downstream oil and petrochemical refinery projects, with Iraq supplying crude oil and Egypt and Jordan using their refinery capacity and facilitating export access to Europe.

- Tourism sector: Develop Iraq’s tourism sector, with Egyptian and Jordanian hospitality companies providing expertise and investment. Once the sector is developed, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq can collaborate to market Iraq’s tourism sector and Jordan’s health tourism resources among the ABC countries as well as regionally.

- Construction sector: Help restore Iraq’s physical infrastructure, building on the expertise of Egyptian companies in the construction industry.

- Renewable energy: Explore and collaborate on new opportunities for renewable energy generation and storage, in addition to water desalination, water recycling, and growing crops in harsh environments. There are growing needs for food and energy security within the three countries that can be met through use of green technology.

- Entrepreneurship: Develop a joint digital strategy to open markets for business start-ups, particularly within the fintech industry.

Recommendations

The ABC Agreement is an opportunity for long-term sustainable development in countries that have suffered from external shocks in the last thirty years, and importantly, the leaders from all three countries have shown there is political will to implement economic integration. The following are recommended steps for successful implementation:

- Robust communication strategy for the three parties involved should be designed to highlight the expected benefits from the agreement.

- Institutional development should take place at the early stages of the partnership. The three countries agreed in 2020 to establish a rotating secretariat that guides and monitors the implementation process, and the secretariat should be adequately staffed and overseen by key leaders from each country, to ensure progress is made.

- A multistakeholder engagement strategy should be developed to ensure that stakeholders from the public sector, the private sector, and the local communities are all invited to provide input and reach consensus on mutually beneficial strategies.

- A practical, actionable implementation plan should be put in place. The table above detailing challenges and opportunities highlights the numerous possible high-priority projects to pursue. A detailed road map, along with a clear timetable, should also be developed.

- Narrowing down sectors of focus for each country is essential. Country expertise should be highlighted within the agreement, and an amelioration strategy should be put in place so that specializations can add value in respective local markets.

- In terms of essential sectors, each country should analyze its ratified national strategies, international agreements, and targets, and then map them against the benefits that can be attained from this partnership.

- Unanimous agreement must be reached on key performance indicators as well as follow-up mechanisms to ensure accountability and to track the progress of the agreement’s timeline.

- Looking at what went wrong and what went right in past similar agreements in the region will be instructive.

- The partnership must be treated as an iterative process, with continuous dialogue among the three countries to capitalize on beneficial opportunities as well as address challenges along the way.

The ABC Agreement from Egypt’s perspective

By Racha Helwa

Background

Egypt is a member or signatory of seventy-three different bilateral trade and economic integration agreements. At least eighteen of these agreements are currently active, including the European Union Association agreement, the Qualifying Industrial Zone (QIZ) with the United States and Israel, and the European Free Trade Association Agreement (EFTA).

The recent ABC Agreement builds upon Egypt’s considerable economic and political relations with Jordan and Iraq. In fact, the ABC Agreement echoes a political and economic alliance between these countries from thirty years ago. They—along with North Yemen—came together in a very short-lived partnership called the Arab Cooperation Council (ACC) from 1989 to 1990. The ACC was disrupted by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, but its economic relations with Egypt and Jordan continued.

The ABC Agreement can also be seen as the latest iteration of the New Sham (or New Levant) project2The New Levant Project is a geopolitical alliance between the three countries of Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. The project is similar to the European Union (EU), and other countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Lebanon are expected to join. and other cooperation projects between the three countries. Some of these projects envision participation by other countries in the region. The economic and political attractiveness of cooperation for these countries is easily understood. Egypt is seeking ways to expand markets for its industries and allies for its regional political leadership ambitions. Jordan is a small country in an unstable region, surrounded by larger and more powerful neighbors. Iraq is an oil-rich nation emerging from decades of war and internal strife. It also has long borders and a history of conflict involving Iran and Turkey, both of which are larger, more powerful, and more than willing to interfere in Iraq’s internal affairs to protect their own interests. By cooperating among themselves, the three countries can represent a united political and economic front and a collective 150 million citizens, more than $500 billion in gross domestic product, and access to major trade routes, markets, and economic and political relationships.

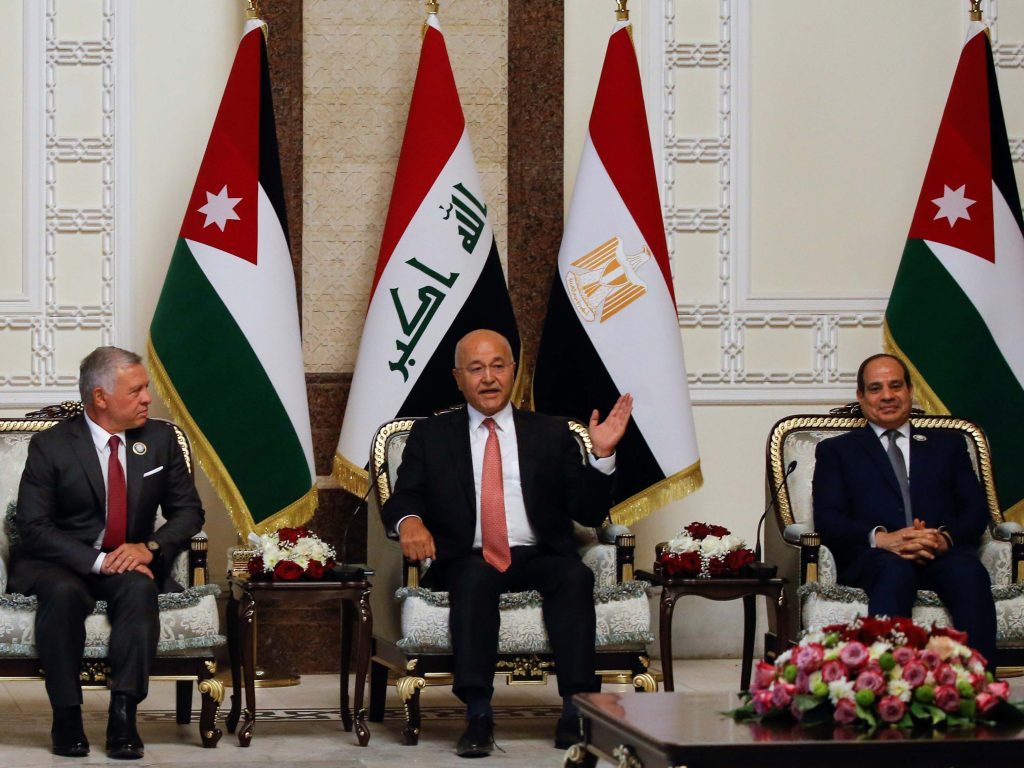

When Egyptian President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi and Jordanian King Abdullah II visited Iraq‘s President Barham Salih on June 27, 2021, the three leaders discussed cooperation across a variety of economic and political areas. These included security matters, regional issues, and specific areas of trade, such as industrial projects, medicine, agricultural products, and the energy sector.

However, the Middle East has a history of optimistic proclamations and agreements that are announced with great fanfare and eventually amount to little. The key factor that will determine the success of the ABC Agreement is whether it can bring tangible, practical benefits to the three participating countries. All three countries face significant economic, political, social, and environmental challenges. By cooperating on projects and linking their markets and policies, they are laying the foundation for potential gains from a stronger combined voice, economies of scale, and scope for specialization. However, this potential will only be realized if the final agreement is not just another optimistic proclamation but instead enacts detailed and specific measures to remove barriers and encourage cross-border cooperation and integration.

For Egypt to maximize the economic gains from this proposed agreement, its government should focus on several key elements of cooperation. The first element is the potential for increased exports of Egyptian goods and services to Iraq and Jordan. The second element is the potential for importing goods and services to Egypt at advantageous prices. The third element is the potential for cross-border cooperation/integration to achieve benefits that the three countries would have difficulty achieving alone.

Bilateral trade relations between Egypt, Iraq, and Jordan

Trade relations between Egypt and Iraq

Currently, Egypt’s trade relations with Iraq are modest. Egypt’s exports to Iraq are limited in size and scope and are mainly centered around electronic equipment, plastics, and iron and steel. At the same time, Egypt’s imports from Iraq are minimal and consist mainly of food products and consumables.

The potential for increased trade between the two countries is significant. Egyptian exports to Iraq can grow substantially in the industries where Egypt is a regional leader, such as construction and financial services. At the same time, given that Egypt is a net oil importer, the ABC Agreement can create a negotiating opportunity to secure a stable supply of oil at a concessional price, minimizing the risk of fluctuations in foreign exchange and sale price per barrel.

Trade relations between Egypt and Jordan

Egypt’s exports to Jordan are primarily focused on oil and minerals, food, and ceramics. At the same time, Egypt’s imports from Jordan remain limited and are primarily centered around fertilizers and chemicals. Therefore, there is significant scope for expanding export/import relations between the two countries.

Maximizing mutual economic gains

The potential economic gains from the tripartite agreement can be maximized with focus on specific import/export sectors. Egypt has a comparative advantage and significant export potential in construction services, infrastructure services (including transportation and telecom), renewable energy, financial services, and educational services. These are all potentially attractive to Jordan and especially Iraq as it rebuilds its infrastructure following the devastation of the last several decades of conflict.

Jordan could also be a market for increased Egyptian exports as well as serve as a link between Egypt and Iraq for the transportation of goods, oil and gas, and electricity. In fact, Egypt recently announced a deal with Jordan and Iraq “for the establishment of a land route connecting the three countries, in a bid to boost economic and trade relations between them.”

Sectors of opportunity for Egyptian exports

Construction

Egypt has a large, highly efficient, and competitive construction industry. Over the last decade Egyptian construction companies have engaged in major projects such as the widening of the Suez Canal, the construction of the new administrative capital, and numerous other projects. Egypt has the most construction projects in all of Africa, “with forty-six projects (9.5 percent of projects on the continent) as well as the most projects by value at $79.2 billion (17 percent of the continent’s value).”

Egyptian companies also have been instrumental in numerous significant construction and development projects internationally. For example, Egyptian companies are building “the Julius Nyerere dam [also called Stiegler’s Gorge dam] and hydropower station, which will be the largest in Tanzania.”

Egypt’s experience with exporting construction services would be particularly attractive to Iraq as it rebuilds its infrastructure. The vast scope of future construction requirements in Iraq—ranging from housing to energy plants to hospitals—likewise create very significant opportunities for Egypt’s construction and infrastructure industry and labor force. Indeed, one estimate notes that “the reconstruction projects in Iraq could provide job opportunities for over two million Egyptian workers.”

Financial services

The financial services and banking sector in Egypt has experienced steady growth due to regulatory reforms in the past six years, including capital requirements, the privatization of public-sector banks, and the consolidation of small private institutions into larger, more robust entities. Fintech services, in particular, are experiencing rapid growth due to recent supportive legislation and significant investments to meet the needs of a sizable population that is still largely unbanked. Egypt’s population exceeds 100 million and 98.8 percent of families own a mobile phone, which gives Egyptian fintech companies the experience and scale to be very competitive exporters to other developing countries.

This experience is potentially very attractive to Jordan and Iraq since these countries’ populations are also largely unbanked and have high mobile-phone penetration rates. Furthermore, in Iraq’s case, the various recent conflicts have hampered the ability of local financial service companies to function, let alone grow and advance.

Telecommunications

Egypt has a relatively advanced and experienced telecom industry that efficiently provides services at low cost. Its geographic location “has enabled it to capitalize on the numerous cables which cross through it, interconnecting various parts of Europe with the Middle East and Asia . . . Egypt offers some of the lowest prices for DSL services on the continent.”3DSL stands for digital subscriber line.

Growth rates and exports in telecom and information technology have been impressive, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, Egypt’s information and communication technology (ICT) sector grew by 15.2 percent in 2020, and exports, from this sector increased to $4.1 billion in 2020 from $3.6 billion in 2019. Similarly, in terms of wireless telecom, there is considerable investment to improve wireless services in Egypt, where up to six thousand new cell phone towers are to be built and utilized over the next three years.

These capabilities would likely be very attractive to Iraq as it recovers from decades of conflict and destruction of infrastructure. Jordan would also benefit from working with Egyptian telecom companies that have achieved economies of scale due to Egypt’s much larger population and service export successes.

Renewable energy

Egypt is a regional leader in terms of renewable energy, especially hydroelectric, wind, and solar energy. The nation boasts considerable experience with projects of all sizes from small scale to some of the largest in the world. Egypt built and has been operating the Aswan High Dam for decades. Currently, it is building the Benban solar plant, “one of the world’s largest solar parks,” at a cost of over $2 billion.

Egypt already exports electricity (and natural gas), and the services of its companies are used in the construction of renewable energy projects in other countries. Indeed, due to its megaprojects, Egypt is one of the main renewable energy producing countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Egypt is looking to export electricity to Iraq through Jordan, to which it already exports electricity. This would potentially be very helpful to Iraq (and Jordan), as Iraq is currently “highly reliant on Iranian gas and electricity imports to meet domestic demand,” and diversifying its sources of energy would be advantageous.

Egypt has put significant emphasis on not just exporting natural gas and electricity, but also exporting the services of its infrastructure companies to develop renewable energy projects in other countries. This has included building dams and solar energy parks in Eastern Africa, as part of Egypt’s diplomatic and economic initiatives related to its dispute with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Egypt’s growing expertise in the construction of significant renewable energy projects and “exporting” that knowledge would be very attractive to Jordan and especially Iraq, as those countries seek to build or rebuild their energy infrastructures.

Sectors of opportunity for Egyptian imports

Due to Egypt’s large population, especially compared to its oil reserves and arable land, the nation needs large amounts of imported oil, fertilizer, and other agricultural chemicals to meet its energy and food-security needs—two key requirements for political and social stability. With a mutually beneficial agreement and a plan for a usable land route linking the three ABC Agreement countries, Egypt could be assured a steady supply of these key products at attractive prices. This would be an expansion of Egypt’s existing imports of oil from Iraq and fertilizers from Jordan.

Opportunities for joint cooperation

Oil and oil derivatives

One of the most important potential impacts of the ABC Agreement would be the cooperation between the three countries to achieve gains that each alone would be unable to accomplish.

One obvious example would be in the oil and oil derivates sector. Iraq currently produces significantly more crude oil than it can refine. With proper infrastructure in place between the three ABC countries, Iraqi crude oil could be shipped in large quantities through Jordan and on to Egypt. This crude oil could then be refined in Egyptian refineries, which currently have spare capacity, to be used locally or exported to Europe and Africa. Or, if the flow of Iraqi crude oil exceeds Egypt’s refinery capacity, the surplus could be shipped to Europe for refining and use.

This scenario would be highly beneficial for all three countries. Iraq faces geographical and political challenges in exporting its crude oil, particularly to Europe. It can ship it through the Persian Gulf, but that is a long, roundabout route that faces potential disruption in any crisis involving Iran and the United States or Arab Gulf countries. It could send its crude oil westward through pipelines; however, political challenges would need to be overcome for it to reach Europe. For example, the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline through Turkey has been shut down since 2014 due to attacks by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS); in September 2021, the Iraqi oil ministry announced that it would be reopened.

Furthermore, Iraq has several significant disputes with Turkey, which has launched frequent bombing raids and incursions against Kurdish parts of Iraq. Other options include sending oil via Syria, which is in a complex civil war, or through Jordan to Israel. Iraq is technically at war with Israel, and any attempt to build such a pipeline would be met with a furious response from Iran and Iranian-aligned groups in Iraq. Therefore, a low-cost, politically and physically secure route for its oil through Jordan to Egypt makes perfect sense for Iraq. It also makes sense for Jordan, which would receive transit revenue and could utilize some of the oil as part of the agreement. It makes sense for Egypt, too, which could use some of the oil and gain refining and exporting revenues from the rest.

The flow of oil could encourage the flow of other trade goods among the three countries. For example, it would be possible to further link these nations’ electricity grids and markets to provide their populaces and industries with resilient electricity supplies.

Education services

Another potential field of collaboration is in the provision of education services. Arab countries historically sent many of their students to Egypt to study, and numerous Egyptian teachers have lived and taught in Arab countries. These flows have decreased in recent years because some Arab countries’ education systems have improved and Egypt went through a period of instability. However, Egyptian universities and institutes are still attractive to many Arab students due to a variety of factors: the relative openness of Egyptian educational institutions to foreign (especially Arab) students; the comparatively low cost of tuition and living in Egypt for them; the lack of cultural or language barriers to living and learning in Egypt for these students; and the comparative quality, breadth, and history of Egyptian educational institutions. In fact, in 2015, the country’s Supreme Council of Universities announced an ambitious plan to quadruple foreign student enrollment from approximately fifty thousand per year to two hundred thousand through outreach to Arab and African students, and improvements to Egyptian universities in the areas of education, research, and student housing.

The provision of educational services was specifically cited by senior government representatives in discussions around the ABC Agreement. Egypt’s rail system is considered comparatively highly advanced for the region, and the Jordanian government expressed a desire to send “Jordanian students, technicians, and engineers to learn in Egypt’s Institute of Ouerdane for rail technology.”

These types of cultural and educational exchanges could be a powerful factor in the success of the ABC Agreement. With proper institutional support, cross-border education can naturally encourage and lead to cross-border cooperation, cross-border companies, trade, services, and more.

The political dimension of the ABC Agreement

As mentioned earlier, the leaders of Egypt and Jordan met with the Iraqi president in June 2021 in Baghdad, the fourth meeting of the three leaders since March 2019. This visit was also the first to Iraq by an Egyptian head of state in about thirty years, which clearly reflects a strong political commitment and a determination for deepening the level of economic and political cooperation between the three countries.

For Egypt, the political motivations behind this agreement are as important as the potential economic gains. First, Egypt believes that it needs strong regional and international support in its water dispute with Ethiopia regarding the GERD, which Cairo views as an existential threat. Second, there have been significant changes in the political map of the Middle East, resulting in a weakening of Egypt’s position in the region following the Arab Spring (although this has recovered somewhat as Egypt’s economy rebounded after the political events of 2011-2013 and the currency devaluation in late 2016). At the same time, Turkey, Iran, and Israel have increased their economic and political influence and relationships in the Arab world (such as Turkey’s intervention in the Libyan civil war), in some cases encroaching on what Egypt traditionally viewed as its sphere of influence.

By more closely integrating their economies and political policies, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq can create an alliance that improves their economic prospects and increases their regional clout, helping them meet a variety of internal and external challenges. This cooperation and integration could also provide a platform to bring other countries into the alliance, such as Syria, as it attempts to end and recover from its own devastating civil war. Syria has historically had deep and occasionally complex relationships with all three of these countries, including a unification with Egypt from 1958 to 1961 and a military alliance with all three against Israel.

Conclusion

The potential for significant political and economic benefits from the ABC Agreement is clear. However, attempts at economic cooperation between Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq are not new. For this latest agreement to be successful, all three parties will need to focus on pragmatic deliverables. In particular, the three countries’ governments should ensure that there are tangible economic benefits for their populations and industries, which would help provide the impetus and support for closer cooperation.

About the author

Racha Helwa is director of the empowerME Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Racha is a senior economist with twenty-two years of professional experience in economic and financial policy analysis and implementation. She has held roles in the private sector, government, and academia in the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Egypt. She specializes in public policy design and implementation, sustainable development, impact investing, and private-sector development. Racha holds a PhD in economic policy from the University of Cambridge, an MSc in international political economics from the London School of Economics, and an MSc in banking, finance, and risk management from the University of Paris. She was formerly an assistant professor of public policy at the American University in Cairo, senior researcher at the University of Cambridge, and senior economist in the Office of the Minister of Investment of Egypt. Racha also has collaborated with various international institutions including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations (UN) Conference on Trade and Development, the UN Development Programme, and the US Agency for Development.

The ABC Agreement from Iraq’s perspective

By Barik Schuber

Introduction

Economic cooperation aimed at gradual integration between Iraq and other Arab countries is highly desirable from Iraq’s perspective. In 2021, the leaders of Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan held their fourth summit in Bagdad to further the new endeavor for economic cooperation and integration, the ABC Agreement.

This section of the report evaluates the new initiative from the perspective of Iraq, examining: 1) the socioeconomic and political conditions in the three countries for initiating a successful and sustainable economic-integration process, 2) the distinctive features of the new initiative between the three countries compared to experiments that have failed during the past six decades, and 3) whether this effort will create a win-win situation for the three countries or win-lose situations for any of the parties.

Historical background and lessons learned

Attempts at Arab economic integration since 1958 have not delivered on government promises to boost economic prosperity.

The first attempt was the Hashemite Federation between Iraq and Jordan, which was initiated in 1958, as a reaction to the pan-Arab state project that was started by Egypt and Syria at same time. A military coup in Iraq five months later aborted this initial attempt, and a second experiment was ended by a similar military coup in Syria in 1961.

There were many fruitless attempts by pan-Arab Iraqi governments during the 1963-1979 period to revive the failed attempt at uniting Arab countries. Then in 1979 the ruling Baath Parties in both Iraq and Syria tried to establish an economic and political union between those two countries, which ended in a massacre inside the Iraqi Baath Party and propelled Saddam Hussein to power as an absolute autocrat.

Another ill-fated union was launched in 1989 between Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, and Yemen; it ended with Saddam Hussain’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Even Arab League initiatives for partial economic integration in certain sectors via the creation of joint Arab companies and institutions have mostly failed to achieve any progress amid the political tensions and instability in the region.

The only exception is the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which was created in 1981. In terms of economic integration, however, the GCC has achieved little. It took the GCC twenty-two years to implement a customs union agreement, where a common external tariff of 5 percent was levied on all foreign imports starting in 2003. Recently, Saudi Arabia has diverged from this agreement by amending its import rules from the Gulf. Moreover, political differences between Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar as well as competing economic interests between Saudi Arabia and the UAE are hindering effective economic integration.

In conclusion, past initiatives and projects for economic integration in the Arab World have failed due to competing economic interests of the ruling classes and political instability such as regime changes. In addition, the private sector in most Arab countries—particularly entrepreneurs who should be the leading force for economic integration—are relatively nascent and weak. In Iraq, the private sector is largely dependent on public expenditure, as is the case in most other rentier economies.

However, the new ABC Agreement cannot be rejected as doomed to fail a priori since present socioeconomic and political conditions in the three countries and in the region are clearly different from the past.

On the national level, all three governments are facing increasing economic and social pressures to improve the living standards of the population. On the regional and international level, globalization and changing geopolitical interests of the former colonial powers—the United States, United Kingdom, and France—and the formation of new political blocs and alliances in the region are changing paradigms.

Iraq’s existing regional trade and economic agreements

Since the 1970s, Iraq has concluded at least twenty-one bilateral trade and economic agreements with Arab states, in addition to some multilateral arrangements within the framework of the Arab League’s Council of Arab Economic Unity.4See Appendix I. Iraq also has trade and economic agreements with Iran and Turkey.

The existing bilateral agreements between Iraq and both countries raise the question of whether the new ABC Agreement is a bundling of past bilateral agreements or something completely new to achieve economic integration of the three economies.

The ABC Agreement should upgrade and further develop existing bilateral agreements by adapting innovative approaches for economic cooperation via joint investment projects, harmonizing technical standards, facilitating knowledge transfer as well as research and development, and promoting solutions to tackle environmental and climate change challenges such as water and food security.

Structure and reform needs of the Iraqi economy

Iraq’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2021 amounted to $4,973, compared with $3,876 in Egypt and $4,394 in Jordan. Iraq’s economic structure differs considerably from both countries due to heavy dependence on crude oil exports.

Economic indicators for Jordan, Egypt, and Iraq

Relatively high oil revenues, albeit subject to frequent fluctuation, have converted the Iraqi economy into an attractive export market for its trade partners despite its inflated public-sector budget and widespread corruption in most state institutions. However, the economy has become less buoyant and subject to frequent external shocks.

In 2019 and 2020, the oil sector accounted for 59.1 percent and 61.4 percent of Iraq’s GDP, respectively, and the rest of the economy is dominated by sectors producing nontradable goods (services, real estate, etc.). In 2020, the share of agriculture in Iraq’s GDP amounted to 6 percent, and manufacturing amounted to only 3 percent. In other words, Iraq’s non-oil exports are practically negligible.

Aside from suffering macroeconomic mismanagement and corruption for nearly two decades, the Iraqi economy faces significant problems related to unemployment as well as weak infrastructure and public services, which have all contributed to causing political instability and civil unrest. At present, the unemployment rate is estimated at about 27 percent and the poverty rate around 25 percent.

Hence, Iraq urgently needs restructuring and diversification of its economy away from oil rent. One major step should be expanding the domestic oil and gas industries to meet local demand for energy sources. Iraq has been importing petroleum products since 2004, costing around $5 billion per year in some previous years between 2006 and 2014. At present, the cost for Iraq’s energy imports totals $2 billion, according to Minister of Oil Ihsan Abdul Jabbar.

Further parallel steps should focus on generating new jobs for the millions of unemployed Iraqis, mainly youth. Heavy investment in infrastructure and productive sectors is urgently needed along with effective measures to eliminate the prevailing corruption.

In 2020, the Iraqi government developed a reform agenda.5The author is the founder and coordinator of the Iraqi Economists Network. This echoes initiatives from previous governments as well as many initiatives from independent Iraqi economists like a symposium organized by the Iraqi Economists Network in 2013 in Beirut.

To implement a reform agenda, Iraq needs international support as well as tangible contributions from the ABC Agreement partners in all sectors of the economy. True reform would entail eliminating the existing structures of corruption and preventing the emergence of new forms of corruption in connection with implementing joint projects such as industrial cities.

Assessment of the main areas of cooperation in the ABC Agreement

Trade gains

Iraq’s import market is relatively large in the region due to high oil revenues in most years since 2004 and limited local production capacity. Iraqi merchandise and service imports were around $72 billion in 2019. The main exporters to Iraq in 2019 were China, Iran, South Korea, and Turkey.

At present, Egypt and Jordan are net exporters to Iraq in terms of goods and services. Egypt’s exports to Iraq amounted to $202 million, while its imports from Iraq were only $5.8 million in 2019. The Egyptian government aims to expand Egypt’s exports to Iraq to around $6 billion. Iraq’s imports from Jordan in 2020 amounted to $478 million, while its exports to Jordan were only $4.4 million.

An expansion of trade through the ABC Agreement may increase exports from Egypt and Jordan to Iraq rather than from Iraq to Jordan and Egypt, since Iraq has very little products to export to both countries, except crude oil which Iraq can offer to both countries at an advantageous cost. However, a trade deficit may be beneficial in the short term to avoid shortages of goods and services, and it may be corrected over time as Egyptian and Jordanian companies expand operations and production in Iraq. Moreover, a larger free trading zone could also attract more international capital to invest in production in these markets.

Investment movement and prospects of project financing

Between the three countries there is no barrier for movement of investment. Indeed, Iraq’s private-sector investments have been flocking into Jordan since the beginning of the 1990s. The total accumulated value of these investments is estimated at $18 billion in four main sectors: manufacturing, real estate, hospitals, and banking.

Apart from pan-Arab companies, there seems to be no Egyptian or Jordanian direct investment in Iraq due to political instability, including Iraq’s war with Iran between 1980 and 1988, followed by its 1990 invasion of Kuwait, and then the international embargo on Iraq from 1990 to 2003.

There has been some skepticism regarding whether the business environment and political situation in Iraq could be conducive to foreign investments, including from Egypt and Jordan, according to Iraqi businessmen interviewed by the author.6The interviews were conducted by the author in confidentiality, and the names of interviewees are withheld by mutual agreement. The interviews took place online through the Economy Elite Business Forum, March 2021. However, a more palatable alternative could be for the three countries to establish a venture capital investment fund for joint projects in Iraq.

Innovative approaches are needed for financing infrastructure projects in Iraq, as the likelihood of public financing by the Egyptian and or the Jordanian government is not promising, due to the high public debt in both countries.

Some have suggested financing infrastructure projects in Iraq through funding from Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf countries, pointing to the announcement from Saudi Arabia and the UAE that they would allocate billions for investment in Iraq. However, this route would entail Gulf countries giving priority to their own national companies to execute projects in Iraq rather than Egyptian or Jordanian companies.

Egypt and Iraq could create a win-win situation through an oil-for-reconstruction deal similar to Iraq’s arrangement with China. Arab financial institutions like the Islamic Bank, Arab Gulf country development funds, the World Bank, and European development banks can also be asked to fund strategic projects that benefit all three countries.

Oil pipeline from Basra to Aqaba and oil processing industry

An oil pipeline running from Basra in Iraq to Aqaba in Jordan was agreed to in bilateral accords in 2013 and 2019, but it is still in the planning and negotiation stage. There also is talk about a possible extension of the pipeline to Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. However, the project has been criticized for its high costs, and for its inability to get Iraq’s crude exports efficiently to its main export destination: Asian markets. Similarly, the new outlet in Aqaba would not effectively minimize the risk of a possible blockade of the Strait of Hormuz. A less costly alternative outlet could be the activation of the old pipeline to Banias on the Syrian Mediterranean coast, and/or the construction of a second pipeline from Haditha to Cihan in Turkey, bypassing the Kurdistan region.

Despite all this criticism, the project may be a win-win situation benefiting the Iraqi economy through the integration of the oil downstream and oil processing facilities in all three countries. In addition, the three countries could consider creating joint investment funds for the rehabilitation and expansion of existing refineries and petrochemical projects as well as launching new initiatives for water desalination in all three countries to meet their increasing local demand for energy and clean water.

Connection of national power grids

The ABC Agreement countries are giving high priority to the connection of national power grids, which makes sense due to the electricity crisis in Iraq. Iraqis frequently suffer power cuts, especially during the hot summers.

However, connecting the grids will not lead automatically to the integration of the power sectors of the participating countries. Harmonizing the sector’s structure and the countries’ energy policy is a prerequisite for any economic integration. To achieve this, Iraq needs power-sector reforms.

Iraq is presently in dire need for tangible measures to mitigate the long-lasting electricity crisis in the country. The shortage is estimated to be between 10,000 and 15,000 gigawatts in the summer. Iraq therefore imports from Iran some 1,200 megawatts (MW) of electricity, as well as some 75 million cubic feet of natural gas, according to the Iraqi minister of oil. However, the actual supply is far less than what is needed or has been sought due to a financial dispute between the two parties.

In the medium- and long-term, Iraq cannot remain dependent on electricity imports from neighboring countries. Economic integration should not mean linking producers with consumers; instead, Iraq should end bottlenecks in the power sector and produce seasonal surplus to be exported to partner countries. Likewise, Egypt and Jordan could export excess capacity to Iraq during peak load in the summer. Cooperation in this field may be a win-win situation for Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan.

Population and labor force movement

The large combined population of the three countries, at about 150 million people, is viewed as a major strength of the new initiative because this sizable consumer market could provide good export opportunities for all the partners. This is true in the case of the effective demand in all three countries, particularly in Egypt, with its population of one hundred million.

Egypt and Jordan currently have a surplus labor force working abroad, mainly in Arab Gulf countries. Iraqis are concerned about plans for two million Egyptian workers to come to Iraq, as happened during the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s. Egypt and Jordan have agreed upon a cheap bus line from Cairo to Amman and on to Baghdad for the transport of Egyptian and Jordanian workers, who are supposed to work in the envisaged infrastructure projects in Iraq.

As mentioned earlier, the latest available data from the Ministry of Planning for the year 2021 indicate an overall unemployment rate of 27%. However, some Iraqi economists estimate that the current rate is much higher due to the coronavirus pandemic. Given this situation and the potential free movement of labor among the three countries, an inflow of Egyptian workers accepting lower wages than Iraqis could put pressure on the wage levels of Iraqi workers, as was the case during the Iran-Iraq War (1981-1988), when some millions of Egyptians worked in Iraq.

Joint industrial city on the Iraqi-Jordanian border

Establishing a joint industrial city as a free trade zone on the Iraqi-Jordanian border was agreed upon in 2019, as a key element of the ABC Agreement.

In 2021, the Egyptian and Iraqi ministers of industry signed an agreement to build joint economic and industrial cities for manufacturing textiles, leather, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural pesticides. The locations of the Iraqi-Egyptian cities have not been defined yet. This is important for assessing the employment effects of each city, particularly in case it is located on the border far away from urban centers, in which case the effect would be fairly limited in terms of employing jobless Iraqi workers. Still, under certain conditions, this mode of cooperation can bring about a win-win situation.

Indeed, there is no information about the preliminary list of locations, which could lead to better understanding of whether the entities to be involved would include existing state-owned enterprises, private-sector companies from the three countries, and/or foreign direct investors from other countries. However, the project is intended to attract private investors from Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq to the zone by removing complicated bureaucratic procedures and including some incentives like tax exemptions. This makes sense for establishing complementary industries with backward and forward linkages.

Questions that need to be clarified include whether investors will be encouraged to create joint ventures or establish their own businesses, and whether producers will be allowed to export their products to the markets of all three countries, without levying customs duties.

Agriculture

Iraq’s agriculture sector has suffered from structural problems for decades, but it has huge potential for sustainable and relatively quick growth rates. Therefore, Iraq’s development strategy should give high priority to upgrading this sector to enhance food security.

Cooperation with Egypt and Jordan on agriculture is highly desirable as both countries have vast experience with modern agricultural technologies and modern irrigation schemes that take into account water scarcity. One possible area of cooperation is establishing large-scale joint ventures in Iraq’s agriculture sector with venture capital and financing from Iraq’s public banking sector. A win-win situation is very likely in this field of cooperation.

Tourism sector

Strangely, Iraq’s many bilateral cooperation agreements with Egypt and Jordan, respectively, have not focused on the tourism sector, and neither does the new ABC Agreement. Iraq would benefit from cooperation with Egypt and Jordan, since both countries has extensive experience in the tourism industry, including business and operational management of large-scale tourism projects. In 2019, Egypt’s tourism sector contributed 5 percent to its GNP while Jordan’s contributed 15 percent. Tourism in Iraq, however, only contributes $955 million compared to the country’s GDP of $207.89 billion.

In the aftermath of Pope Francis’s 2021 visit to the birthplace of Abraham near the ancient city of Ur in what is now southern Iraq, the potential to attract a new type of religious tourism, combined with visiting historical and archaeological sites as well as the exotic marshlands in southern Iraq, has improved considerably. Some thirteen thousand pilgrims were expected to visit the site in 2021, according to an Iraqi official. Therefore, the Iraqi government is planning to build a new airport near that ancient city. Investments in modern infrastructure for tourism and management know-how are needed to develop this sector, which can contribute to the diversification of the economy. Therefore, the Iraqi government should make tourism a key area of cooperation via the ABC Agreement and attract Egyptian and Jordanian private investors to initiate joint projects with the Iraqi private sector in promising areas such as the Marshlands and the archaeological sites near the ancient city of Babylon and Uruk. A win-win situation is very likely in this field of cooperation.

Conclusion and recommendations

Iraq is divided on the future vision of its economic structure. The ruling class and its clients prefer the status quo of the rentier economy based on increasing crude oil exports and revenues, which also leads to corruption and a clientele economy.

Iraq’s oil minister declared recently that oil production will be increased from the current production level of approximately 4.5 million barrels per day to 8 million barrels per day by 2027.

In contrast, Iraqi economists and some reform groups inside and outside government institutions have been advocating for the diversification of the economy as an important remedy for the recurrent economic shocks that Iraq has been subject to in reaction to oil price volatility. More than seventy documents on macroeconomic and sectoral development strategies have been published over the last sixteen years, but very few have been implemented. The recently announced white paper by the Iraqi government provides a possible road map for initial economic reform measures needed in the near future.

Given Iraq’s poor track record with economic reforms, as well as the numerous past agreements among Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan that have not reached significant results, the ABC Agreement is unlikely to mark a turning point unless there is serious and concerted implementation effort. One possible spoiler is Iraq’s political instability. Iraq held elections in 2021, but political disputes within the ruling class continue as the losing parties refuse to accept the result and escalate their protests against the winners. Even if the competing factions reach a compromise, it is not clear how the new government in Iraq will view or act upon the ABC Agreement.

Despite these challenges, economic cooperation and integration between Iraq, Egypt, and Jordan should not be abandoned. The ABC Agreement should be developed carefully to ensure a win-win formula for all involved partners. It should also offer the opportunity for new members to join, such as Syria and Lebanon, to help address the economic crises in both countries. International experience has shown that economic integration can follow a challenge pathway and may require a detailed and well-structured implementation road map.

As a first step, the three countries could consider initiating one or two joint-pilot projects in target industries, to explore the potential for economic integration in these sectors. The most important candidate from the Iraqi point of view is the oil and gas industries in all three countries, and then the agriculture and the tourism sectors.

Exploring joint activities in the oil and gas sector in all three countries, such as gas processing, oil refining, and petrochemical production, could benefit Iraq particularly given Iraq’s limited refinery and processing capacity and resources. Iraq’s main role would be the provision of crude oil at discounted prices. Establishing a customs union would allow free trade flows of oil and petrochemical products between the three countries and enhance exports to the world market. Furthermore, creating a joint investment fund for private-sector investments and establishing a high commission to manage the new partnership would both be prudent moves.

After several years of successfully implementing and assessing these initial steps, further unions in other fields of the economy could be initiated.

About the author

Barik Schuber holds a master’s degree and PhD in economics, sociology, and political science from the Universities of Frankfurt/Main and Marburg/Lahn in Germany. He specializes in macroeconomic management and development planning as well as sector analysis and project management. He worked for seven years as a research fellow at the Department of Social Sciences at Philipps University of Marburg. From 1980 to 1985 he was engaged in private-sector trading and consulting activities. In 1985 he joined the German Agency for International Co-operation (GIZ, formerly GTZ) and was seconded to the Ministry of Planning in Saudi Arabia as economic adviser to the deputy minister. He was responsible for advising him in the preparation and follow-up of the Five Years National Development Plans. In 1996 he started a new position as project planning and management officer at the Department of Energy and Transport in the headquarters of GIZ in Eschborn, Germany, where he was responsible for planning and management of energy efficiency and renewable projects in various developing countries. In 2004 he was appointed acting head of the Department of Economic and Social Studies at the Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research in Abu Dhabi. In 2005 he was engaged in supporting private-sector organizations and served as secretary-general of the Iraqi Business Council in Abu Dhabi. During 2006 and 2007 he worked as an international expert for a European Union-funded project in Egypt, with responsibility for planning, implementing, and coordinating a study on the macroeconomic framework for reforming the national technical and vocational education and training system. Since 2007 he has been working as a consultant on international development cooperation in the Middle East and North Africa region, particularly with Iraq. He is founder and coordinator of the Iraqi Economists Network, a nongovernmental organization.

The ABC Agreement from Jordan’s perspective

By Ibrahim Saif

Background

While the ABC Agreement brings to mind the short-lived ACC of the late 1980s, the new initiative is a fundamentally different endeavor.

Jordan sees the 2019 agreement as a route for regional cooperation that could encompass large-scale industrial projects, promote trade, and help develop other industries including agriculture. The agreement could also maximize Jordan’s potential as a strategic trade intermediary given its location right between Egypt and Iraq, and can also help promote Jordan’s position as a key logistical hub for the entire MENA region. Examples of other regionally based economic blocs include the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a trade zone, and the economic union of Benelux, which began as the customs convention of Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Commitments under the ABC Agreement will be institutionalized and monitored by a steering committees which will be nominated by the three countries. The three countries have also discussed forming an Executive Secretariat, with a rotating chair every year/multiple years.

A summit for the countries’ leaders was held in Cairo in 2019, followed by two more summits: in New York in 2019, and Amman in 2020. In June 2021, King Abdullah II and President el-Sisi joined Iraqi President Saleh for a summit in Baghdad, the first visit by an Egyptian president to Iraq since the early 1990s. A general statement highlighting potential areas for economic collaboration between the three countries has also been issued.

Maximizing political gains from the ABC Agreement

The MENA region as a whole is facing unprecedented economic uncertainty, with dwindling resources amid falling oil prices as well as protracted social turmoil. The increased instability in Iraq since the start of the Iraqi-Kuwaiti war in the 1990s, followed by the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, has triggered political uncertainties in other neighboring countries and in the region as a whole. Moreover, the absence of a political settlement in Syria and increasing sanctions on the Assad regime continue to suffocate a key trade route for Jordan. Free trade agreements and investment “trilaterals”—not only with Iraq and Egypt, but also with Cyprus and Greece, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain—have been of interest to Jordan as a way to stimulate business and trade opportunities.

Political, economic, and security conditions are a major impetus for these new avenues of cooperation:

- On one hand, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) members, and Saudi Arabia in particular, are adopting modernization measures via Vision 2030 and similar national development plans. In order to diversify their sources of economic growth, GCC countries are attempting to shift from conventional resource-based economies to more sustainable economic activities, with a focus on entrepreneurship, tourism, investment, and digital transformation.

- On the other hand, other Arab countries have been burdened by a plethora of different challenges. Syria was a major trade partner for Jordan for many years; however, due to internal conflict, Jordan lost a substantial market that enhanced its national exports as well as access to a hub for exports to different regions. In Lebanon, the local currency has lost 90 percent of its 2019 value, poverty rates exceed 70 percent of the population, and the political will to address these issues and enact reforms is nonexistent. In addition, countries like Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, and Morocco have all suffered from regional conflicts and fallout from COVID-19, leading to diminished intra-industry trade volume and increased unemployment rates.

The variation between the needs and approach of GCC states versus other countries in the region has led to a disparity in economic priorities that may not align in the foreseeable future. They also reflect the inability to access GCC membership, the weakness of Arab League economic integration, and the growing assertiveness of new international and regional economic actors such as China, Turkey, Iran, and Russia. Regional integration has also historically been one of the major deterrents for interregional conflict due to the high interdependence of the involved countries. Combined, these factors explain Jordan’s desire to expand trade with two of the largest neighboring markets and key energy partners: Egypt and Iraq.

Potential economic gains from the ABC Agreement

Trade in commodities

Each country in the ABC Agreement must capitalize on its specializations. In terms of exports, Jordan seems to be in a good position to specialize in the sectors of travel and tourism, potassic fertilizers, transport, ICT, and packaged medicaments.

Given Jordan’s experience producing these products, Jordan can take advantage of the regional integration to start producing a group of commodities. This is an opportunity to diversify its export portfolio given that there is high demand from the Egyptian and Iraqi markets, based on their import portfolios.

Moreover, Iraq and Egypt are among the five countries that are geographically closest to Jordan. Therefore, Jordan could benefit from Egypt as an enabler to expand Jordanian exports into other African countries.

Export market diversification

In 2019, Jordan exported domestically produced commodities to a total of 146 markets globally. However, 57 percent of the value exported was concentrated in four countries only.

The fact that Iraq is one of Jordan’s four main export partners proves that there is a promising opportunity for Jordan and Iraq to collaborate in accessing other markets (particularly those in Southeast Asia) given their existing strong trade relations. On the other hand, the low exporting volume to Egypt, coupled with the relatively low market concentration in sub-Saharan Africa, points to the possibility of Egypt’s role as an entry point to the sub-Saharan market for Jordan.

Jordan and Egypt have similar trade profiles. Removing trade barriers between the two countries under the ABC Agreement may lead to trade diversion rather than trade creation. Therefore, economic diversification could help both countries improve their product mix and create better trade opportunities, regionally and bilaterally. collaboration to diversify the product mix is essential to promote healthy competition and specialization.

Trade in services

Jordan’s information and communications technology services sector is one of the most developed sectors in the region. According to the Ministry of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship, “Jordan contributes 75 percent of the Arabic content on the Internet.” In addition, data science, cybersecurity, and programming services are now of high importance for Jordan as they are aligned with Jordan’s Digital Transformation Strategy. Within the partnership, such services can be utilized to support the Egyptian and Iraqi governments in automating and digitizing some of the government services that have already been established in Jordan.

Jordan’s engineering and construction services are also competitive regionally, particularly due to the large Jordanian engineering firms that have a strong presence in GCC countries and other areas around the world. Jordanian engineering consulting firms were involved in the redevelopment and reconstruction of areas that were affected and/or destroyed by the conflict in Iraq, and the majority of these projects were funded by international financial institutions and the international community.

The tourism sector was a key target of Jordanian government investment in the pre-COVID-19 era. This sector, combined with Jordan’s highly developed healthcare system, has made the country regionally competitive for health tourism services. Indeed, there has been a steady increase in the number of health tourists visiting Jordan over the last decade. This has led the government, in collaboration with the private sector, to develop plans and incentive packages for tourists to maximize local consumption during their stays. The ABC Agreement can be useful to Jordan in terms of promoting and expanding its healthcare tourism industry.

Given Jordan and Egypt’s extensive expertise in the tourism industry, they can collaborate with the Iraqi government to help restore this important sector in Iraq. The latter’s rich history can be capitalized on by creating/redeveloping historically and archaeologically significant tourism sites.

Investment opportunities

Investment climate

Promoting a competitive business climate in Jordan has been a challenge. Investors in Jordan have numerous concerns relating to energy costs, policy unpredictability, and the significant lack of skillful workers. This has translated into a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, as well as local investment.

On the other hand, Egypt’s FDI inflows as a percent of GDP have been increasing since 2012, despite the political instability that followed the Arab Spring. Egypt has also been one of Jordan’s major competitors, especially in the textiles sector. A collaborative effort using the ABC Agreement may lead to mutually beneficial growth, which might not be fully achieved within the current competitive landscape.

Helping more start-ups and new products survive

The longevity of new investments in any country is predicated on the enabling conditions that allow investors to scale up their business. Unfortunately, introducing new products to the three countries’ respective export baskets has not been successful in recent history. In 2013, Jordan introduced approximately 474 new products to its export basket. By 2018, only 44.5 percent of these products had survived.

This has also been a challenge for Jordanian start-ups whose average lifespan is around three years. Aside from a few anomalies that have scaled up in recent history, most start-ups have either maintained (i.e., observed no improvement or scale-ups) or terminated their operations.

An economic integration of Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq that operates with clear parameters, policies, taxes, and requirements could incentivize the production of larger product quantities as well as the introduction of new products in the long run. The integration would give all three countries the ability to collectively negotiate with major trade partners around the world, which could in turn increase the survivability of commodities.

Employment opportunities

Jordan’s increasing rate of unemployment, particularly among women, is a major challenge. What is especially concerning is that a higher level of educational attainment is associated with higher difficulty in finding jobs. To address this issue, Jordan can take advantage of the trilateral integration to introduce innovative and sophisticated goods and services through new online platforms for interregional trade.

The services sector can benefit from highly skilled people with tertiary educational attainment who are struggling to find job opportunities suited to their skill sets. Many recent graduates resort to jobs that are unrelated to their university degrees due to the supply-demand gap that has ailed Jordan for years, particularly in the engineering and medical fields.

The main enabling sectors for the ABC Agreement

Transportation

The transportation sector is one of the main enablers for the trilateral trade agreement. The costs of transportation are pivotal in determining to which international markets to export. Jordan’s land transport costs for commodities are highly competitive compared to Iraq at a price of approximately $3 per unit per 10,000 kilometers (km), compared to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, and Turkey, whose costs range between $5.8 and $84.5 per unit per 10,000 km.

On the other hand, transportation costs in Egypt are highly competitive relative to Jordan. The Egyptian transportation system is globally competitive in terms of quality of infrastructure and the connectivity of different modes of transportation. Should there be a partnership between the three countries, Jordan has a significant opportunity to export its products to European and North African countries through Egypt, thereby decreasing the overall costs of its domestically produced commodities.

It is also important to focus on the mobility of individuals. Under the agreement, improvements can be made by enhancing the role of the Arab Transport Co. and instituting cross-border collaboration for unified ticketing and modes of transportation, particularly those involved in the proposed Unified Economic Zone between Jordan and Iraq.

In terms of improving the maritime transport system, the three countries agreed on a twinning mechanism for the respective academies for maritime studies during the trilateral summit of June 2021, which is an essential step to empower the respective ports, increase their competitiveness, and improve their operating efficiency.

Energy and water

All three countries in the ABC Agreement are considering working on an electric grid interconnection project to enhance the stability and reliability of electricity networks and establish a joint power market in the Arab world.

As of September 2020, Jordan and Iraq have agreed to fully connect their electric networks by the end of 2022. Both countries are expected to look into increasing the capacity of the Amman-Qaem interconnection as well as strengthen the existing Jordan-Egypt interconnection.

Jordan has a surplus in power generation and is able to export some of these resources to neighboring countries. Iraq has signed an agreement with General Electric to scale up power infrastructure inside Iraq, and the Jordanian infrastructure is ready all the way up to the shared border. The project in Iraq could be completed by the end of 2022, and negotiations regarding the tariffs and related issues are underway between the governments of both Iraq and Jordan. Egypt has little to do directly with this project before completion of the connection between Jordan and Iraq.

In 2013, Iraq and Jordan planned to build gas and crude oil pipelines to begin at Basra and end in Aqaba. However, the mounting regional instability has slowed down the process. In 2017, the gas pipeline plan was canceled to reduce costs and to expedite the construction of the crude oil pipeline project. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the May 2020 bidding deadline for the project was postponed as well. Iraq and Egypt have discussed expanding the pipeline to Egypt, and recently officials from the three countries have resumed talks about this project. However, there is still no clear road map.

These plans directly impact energy security for all three countries. Due to conflict, Iraq’s energy security is low, as shown in the Energy Trilemma Index. According to the index, energy security is comprised of three main categories: import independence (in which Egypt and Iraq have performed exceptionally well), diversity of electricity generation (in which all three countries have performed relatively poorly, despite the fact that Jordan is the third most improved country in this category), and energy storage, which is defined based on the country’s ability to meet its demand for oil and gas given the existing level of infrastructure including storage and refining facilities. In energy storage, all three countries have scored below the world average. Therefore, if Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq are able to deepen their economic collaboration efforts, all three countries could improve their energy security profile.

In the water sector, this has been an area of concern for Jordan for many years. The situation remains dire given the significant population increase rate in Jordan, and provided that Jordan’s economic activities are water intensive. In fact, the industrial sector, which constitutes around 17 percent of GDP in Jordan, is the most threatened in terms of water security.

Iraq’s water situation is very similar to Jordan’s. However, the outlook on the Egyptian water sector is better, suggesting an opportunity in terms of water supply on the Egyptian side and desalination opportunity on the Iraqi and Jordanian sides.

Jordan has been working with donor agencies to establish the Aqaba-Amman water desalination project (also known as the National Water Carrier Project). The first phase of this build-operate-transfer project is expected to reach a maximum capacity of 350 million cubic meters. To contextualize in numbers, the overall water storage in all of Jordan’s dams (excluding aquifers and the Disi water-supply project) reached 95 million cubic meters, constituting 28.2 percent of Jordan’s overall capacity of 336.4 million cubic meters.

Potential joint projects

Unified economic zone on the Jordanian-Iraqi borders

The Jordanian and Iraqi governments are set to establish a Unified Economic Zone (UEZ) on the Jordanian-Iraqi border. Land allocation, financing instruments, and institutional arrangements are ongoing, and the Jordanian government is planning to create a task force for the project, with the participation of public and private sector leads.

So far, the UAE, Turkey, and China have been the largest exporters to Iraq (around 62 percent of total Iraqi imports come from these three countries), whereas Jordanian exports only constitute 1.58 percent of Iraq’s total imports. Policies (adopted in Iraq) were put in place to limit imports from Turkey. Establishing the UEZ between Iraq and Jordan may help position Jordan as a key exporter to the Iraqi market.

The establishment of the UEZ is an opportunity for a new trade narrative in the MENA region. The concept of interdependence is essential for local and regional security in the long run. In fact, developing the UEZ could offer a unique opportunity for the two countries to improve their food security position, and improve their total factor productivity.

Regional center for food security

Jordan submitted a proposal to Egypt and Iraq in December 2020 to increase trade in a variety of products, including agricultural products.

This element of the partnership is especially relevant for Iraq since approximately 6 percent of Iraq’s population is in “acute need for food and livelihood assistance,” according to the UN World Food Programs.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of food security for all three countries. In Jordan, full lockdowns presented unprecedented challenges for food supplies as well as local food and agricultural production. Should a new crisis emerge that truncates local production and food imports, the three countries can have a joint strategy that allows for readily available supplies.

Jordan and Egypt rank 49 and 62 out of 113, respectively, in the 2021 Global Food Security Index, and if customs and import tariffs are unified within the ABC Agreement, Jordan’s agricultural exports to Egypt are expected to increase. Jordan could also provide dietary diversity to Egypt.

Furthermore, both countries have ample room for improvement in agricultural financial services, including:7Assessment based on World Food Programme data and the Global Food Security Index rankings (discussed above).

- Improving market access and agricultural financial services

- Streamlining access to finance and financial products for farmers

- Consolidating access to diversified financial aid and services

- Enhancing access to market data and initiating new flexible banking services

Conclusion

The ABC Agreement is an opportunity for long-term sustainable growth in countries that have suffered from exogenous shocks in the last thirty years and, more importantly, leadership from all three countries have shown there is political will to implement economic integration. Implementation requires meticulous legwork based on collaborative effort. To sum up, the ABC agreement could provide a unique basis for economic integration in the region. The three countries must capitalize on this first step towards the initiation of the agreement.

About the author

Ibrahim Saif is Vice President of the Manaseer Group and former CEO of the Jordan Strategy Forum, a leading economic development think tank in Jordan. Previously, he served as Jordan’s minister of energy and mineral resources from March 2015 to June 2017, and as minister of planning and international cooperation from March 2013 until March 2015. Prior to his appointment as a minister, Saif was a senior scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center, and served as a consultant to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and other international organizations. Saif earlier served as director of the Centre for Strategic Studies at the University of Jordan and as the secretary-general of the Economic and Social Council in Jordan. He has taught at both the University of London and Yale University on the economies of the Middle East.

Image: Iraqi President Barham Salih and Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi meet with King Abdullah II of Jordan and Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, in Baghdad, Iraq, June 27, 2021. REUTERS/Khalid al-Mousily