Welcome to the group chat. On Monday, the Atlantic (no relation) published an article by its editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, revealing that senior Trump administration officials had added him, apparently accidentally, to a sensitive discussion on the encrypted messaging service Signal about upcoming strikes on the Houthis in Yemen. On Wednesday, Goldberg released more messages that gave a fuller sense of the discussion. The still-unfolding revelations, which have sparked heated debates in Washington and dominated the news this week, offer perhaps the clearest picture yet of how President Donald Trump’s top officials are thinking about US foreign policy—and well beyond Yemen. Below, Atlantic Council experts offer their emoji-free insights on the biggest lessons to take away from these developments.

Click to jump to a lesson:

What did we learn about US Middle East policy?

What did we learn about how this White House views Europe?

What are the intelligence implications of this leak?

What are the information-security implications of this group chat?

There was a big debate in the chat about who benefits from the Suez Canal. What is the real story?

What did we learn about the campaign against the Houthis?

What did we learn about US Middle East policy?

We learned that while there are predictable differences within the Principals Committee, Trump is clearly calling the shots. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth cited the “POTUS directive to reopen shipping lanes,” while Homeland Security Advisor Stephen Miller recalled that “the President was clear” and Vice President JD Vance noted that “the strongest reason to do this, as POTUS said, was to send a message.”

This exchange revealed a group of senior officials primarily focused on executing a presidential decision, not working to undermine or reverse that decision, as was often the case during the first Trump administration. Even Vance’s somewhat condescending comment about his boss (“I’m not sure the President is aware how inconsistent this is with his message”) was quickly followed by a preemptive retreat (“I am willing to support the consensus of the team and keep these concerns to myself.”) Trump is undoubtedly pleased by the stark difference from his prior experience during his first term with then Secretary of Defense James Mattis, then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, then Chief of Staff John Kelly, and the other “adults in the room.”

Trump made the right decision to attack the Houthis to defend freedom of navigation through critical maritime chokepoints, an action I have encouraged for years. (I would prefer a sustained, lengthy special operations–led air campaign against Houthi leadership, rather than the more expensive conventional approach recommended by US Central Command, however.) Trump is similarly correct in his frustrations that governments in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe (with the United Kingdom being the exception) have thus far largely refused to share the burden of reopening the sea lanes. Trump deserves credit, however, for not allowing those understandable frustrations to prevent him from carrying out these duties—as National Security Advisor Michael Waltz aptly summarized in the group chat: “we have a fundamental decision of allowing the sea lanes to remain closed or to re-open them now or later, [and] we are the only ones with the capability.”

But Trump, now mirrored by certain members of his team, remains fundamentally wrong in his minimization of continuing vital US interests in the Middle East. As the world’s largest importer and second-largest exporter, the United States would be disproportionately hurt by any abandonment of the principle of freedom of navigation. Any sharp and unexpected increases in the globally traded price of oil—a price that is directly affected by stability in the Middle East—causes inflation to rise in the United States. Diminishing Houthi capacity to project power, especially in the wake of Israel’s successful campaigns to diminish Hamas and Hezbollah’s ability to do so, further limits Iranian power in the region, a factor that may be critical if a nuclear crisis with Tehran emerges on Trump’s watch. The United States projects its own power in the region first and foremost because it helps secure US economic and national security interests and not as a gift to others—and certainly not, as Miller put it in the group chat, in order to get “some further economic gain extracted in return.”

For many decades, across Republican and Democratic administrations alike, US presidents have all understood this. But Trump’s contrarian views on this subject are clear, long-standing, and well documented. Indeed, even back when Trump announced the first of the Abraham Accords from the Oval Office—one of the crowning achievements of his first term—he still couldn’t have been clearer: “We don’t have to be there anymore. We don’t need oil . . . We no longer have to be there. It started off when we had to be there, but as of a few years ago, we don’t have to be there. We don’t have to be patrolling the straits. We’re doing things that other countries wouldn’t do. But we put ourselves, over the last few years, in a position where we no longer have to be in areas that, at one point, were vital. And that’s a big statement.”

Indeed. And now that Trump has assembled an administration that truly allows him to call the shots, nobody in the region should be surprised by the direction of policies to come.

—William F. Wechsler is the senior director of Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council. His most recent US government position was deputy assistant secretary of defense for special operations and combating terrorism.

***

One of the least-remarked-upon aspects of the US strikes in Yemen against the Houthis has been the strategic justification for the strikes. Besides Trump’s statement on March 15 at the start of the strikes, Hegseth articulated a justification for the strikes that carried with it strategic continuity that aligns with decades of US national security policy. Hegseth noted that the strikes were principally about freedom of navigation and restoring deterrence in the Middle East region.

These principles transcend individual presidential administrations. Then US President Joe Biden’s statements at the 2022 US-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Summit contained these principles, as did Trump’s statement at the 2017 US-GCC Summit. Historically, Hegseth’s thinking can trace its lineage from the Roosevelt administration to the Eisenhower administration and the United States’ leading role in shaping the security of the Middle East region. This policy eventually evolved with the Carter and Reagan administrations’ efforts to counter the hostile nature of a revolutionary Iran. The Trump administration’s bombing campaign is the latest manifestation of this approach. Whether it is acknowledged or not, there is considerable strategic continuity in the most recent US military actions in the region.

—Daniel E. Mouton is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative of the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He served on the National Security Council from 2021 to 2023 as the director for defense and political-military policy for the Middle East and North Africa for Coordinator Brett McGurk.

What did we learn about how this White House views Europe?

Most European observers will take these revelations as confirmation of what they sensed before—that parts of this US administration are reflexively anti-European. This anti-European camp prefers to beat up on allies on the continent over addressing real and significant challenges. It reduces Europeans to a caricature of free-riders. It does not grasp the complex, 9.5 trillion-dollar economic integration and interdependency between the United States and the European Union (EU). And it views decades-old alliances as zero-sum games, if not a protection racket-like arrangement. And while this camp eschews foreign entanglements, it also shows an almost childish fascination with the unconstrained exercise of US hard power. Administration officials with these views are among the most senior in Trump’s cabinet.

But European decision makers should take away a few more insights and—most importantly—action items from the exchange. For one, there are officials in the Trump administration who do understand the importance of freedom of navigation and just how integrated global shipping, transatlantic supply chains, and US-EU trading relations are. That’s something to build on as the United States and the EU are on the brink of a trade war, likely to undercut each other while benefiting strategic competitors. Second, Europe will not be taken seriously by this White House until it develops some key capabilities to take care of its own core national security interests. In the current debate, European leaders should take this as further motivation to think big, get ambitious, and move fast to address defense spending, capability gaps, and defense-industrial shortcomings. Third, Europeans should be ready to throw these free-rider comments back at the White House when it inevitably criticizes Europe for requiring moderate levels of European taxpayer money for new military budgets to be spent on buying European.

—Jörn Fleck is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

***

One of the most pronounced themes in the exchange is its overall negative attitude toward Europe. The continent is referred to in the chat as “pathetic” and “free-loading,” suggesting that relations with Europe are increasingly seen as a burden. Since these private comments are now public, they are likely to strengthen the already negative attitudes toward the United States emanating from the capitals of the largest European countries. It is also striking that in the discussion, Europe is treated as a unitary actor, with no differentiation between individual allies, some of which, like those in NATO’s northeastern corridor, have done precisely what Trump has asked for all along: increased their spending on defense. It remains to be seen whether and how those Eastern flank countries will react, and if this exchange will impact their policies going forward.

—Andrew Michta is a senior fellow and director of the Scowcroft GeoStrategy Initiative at the Atlantic Council. The views expressed here are his own.

What are the intelligence implications of this leak?

The Atlantic’s publication of the near-complete Signal chat by Trump administration officials discussing plans for attacks against the Houthis may negatively affect the United States’ ability to collect intelligence against the Houthis and enable the militant group to better prepare for future US military operations. The exposure of the Signal chat may put any US human sources at risk, as well, because the Houthis are likely to suspect that the United States’ ability to strike certain Houthi military targets and individuals also comes from information provided by insiders. Finally, the Houthis may be able to glean from the sequencing of US military operations described in the Signal chat ways to better position Houthi assets to mitigate the effects of future US attacks.

But there may be a silver lining for the United States, as well. The reference in the chat to the specific movements and locations of Houthi officials will undoubtedly prompt the group to try to tighten up the way its members communicate with one another, particularly regarding how and when cell phones can be used. While the negative consequences for the United States are potentially significant, Houthi concerns about their communications and spies may play to the US advantage. If the Houthis reduce their use of cell phones, and perhaps rely instead on passing verbal or written messages, it will slow the group’s response to threats. And Houthi internal spy hunts are likely to create suspicion and mistrust within the organization, which could undercut the group’s military effectiveness.

—Alan Pino is a nonresident senior fellow with the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs. He previously served for thirty-seven years at the Central Intelligence Agency, covering the Middle East and counterterrorism.

What are the information-security implications of this group chat?

I spent two years as a National Security Council staffer who helped to coordinate Principals Committee meetings on counterterrorism policy and operations. The United States government allocates enormous resources and capacity to make sure national security deliberations and decisions—and the personnel impacted by both—are kept safe. The use of a publicly available messaging platform and the inadvertent inclusion of a prominent journalist in an operational counterterrorism decision is a stunning breach of security. Three things stick out.

The first issue is the technical risk. Signal is one of the more secure-by-design encrypted messaging apps with forty million to seventy million monthly active users. It’s a great app that prioritizes privacy, but the platform’s design pales in comparison to the security footprint and communications infrastructure that senior US officials travel around the world with to ensure they can communicate securely.

The second issue is operational risk. Decisions, deliberations, and the information that feeds both are typically classified. The substance of the leaked chat seems to contain all three.

The third issue is good governance. Parts of the leaked Signal chat were set to automatically delete after one week, with others disappearing after four weeks. Communications by government officials about government decisions, like counterterrorism operations, are subject to laws like the Presidential Records Act to ensure transparency and oversight of government is possible. Not having a record of one of the most serious national security decisions an administration can make is a hindrance to the transparency and accountability expected in a functioning democracy.

—Graham Brookie is the Atlantic Council’s vice president for technology programs and strategy, as well as the senior director of the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab).

***

The “Houthi PC Small Group” chat is one of the most revealing windows into real-time US national security policymaking since the release of the Kennedy-era Cuban Missile Crisis tapes. Of course, the Cuban Missile Crisis tapes were released twenty years after the fact and following exhaustive legal review. The internal deliberations of the Trump-era Principals Committee were revealed while the bomb remnants were still smoldering and because no one thought to check the Signal chat’s participant list.

There are two clear implications for US national and information security. The first is that the personal devices of senior US national security officials—always a focus of foreign actors—have almost certainly become the highest-priority collection target in the world. If these senior-most policymakers are sharing this much information on commercial systems, it begs the question of whether other appointees are sharing sensitive information on platforms such as Signal—or even less cryptographically secure apps.

The second implication is the deeply demoralizing effect that this scandal will have across the US defense and intelligence professional apparatus. The specific operational information shared by Hegseth is always marked at least the Secret level and releasable in only rare instances. The information is not classified at a higher level only because US military components must be ready to act on it and may not have access to the most secure communications in the field. What Hegseth shared—a complete operational snapshot two hours before US air strikes commenced—is only ever supposed to be known to a few dozen decision makers. It only belongs on government systems and certainly not in a journalist’s messaging app.

Service members and defense and intelligence professionals have collectively spent millions of hours learning how to safeguard sensitive national security information. Many are left wondering why they face the threat of immediate expulsion or imprisonment for mishandling such information if there is no accountability at the top.

—Emerson T. Brooking is director of strategy and resident senior fellow at the DFRLab of the Atlantic Council Technology Programs. From 2022 to 2023, he served as cyber policy advisor within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, where he was an author of the 2023 Department of Defense Cyber Strategy.

***

Signal is known for its robust end-to-end (E2E) encryption, often considered the most secure by default among messaging apps. The Signal encryption protocol is trusted to protect messages from unauthorized access during transit and at both ends of conversations. However, the Houthi Principals Committee group chat incident underscores that even robust E2E encryption like Signal’s is insufficient for US cabinet-level discussions, particularly military operation planning.

Several factors contribute to this inadequacy. While encryption secures the content, it doesn’t address operational and physical security risks associated with using consumer apps on personal devices. High-ranking officials using mobile phones in potentially unsecured environments expose themselves to greater surveillance and interception risks.

This case also demonstrates critical user behavior pitfalls. Displaying full names and accidentally adding unauthorized individuals to sensitive chats nullify the intended security of any encryption protocol. No encryption can prevent such human errors.

Finally, regardless of encryption, discussing highly sensitive military and national-security topics on mobile phones inherently carries cybersecurity risks. The ease with which personal mobile devices can be compromised poses a significant threat to classified information. Government communication systems employ far more extensive security measures than consumer apps. The use of personal phones and unauthorized apps can easily be exploited by adversarial actors with communication-interception capabilities.

—Iria Puyosa is a senior research fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Democracy+Tech Initiative.

There was a big debate in the chat about who benefits from the Suez Canal. What is the real story?

The Suez Canal is not just a European concern—it’s a critical global artery that benefits the entire world, including the United States. While only about 3 percent of US trade passes through the canal directly, that figure understates the canal’s broader strategic and economic relevance. Around 30 percent of global container traffic and 40 percent of Asia-Europe trade flows through the Suez, much of which is embedded in US-linked supply chains. What happens in the canal affects global shipping costs, manufacturing inputs, and ultimately US businesses, consumers, and inflation levels more broadly.

The canal is also a key conduit for global energy flows, with around 9 percent of global seaborne oil flows and 8 percent of liquefied natural gas (LNG) volumes passing through it. Disruptions lead to price spikes and increased volatility in global energy markets, which directly impact US economic stability and consumer prices.

Beyond economics, the canal holds military importance, enabling rapid US naval deployment between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. The Signal chat’s dismissive tone about its importance reflects a narrow understanding of global interdependence. The Suez is a strategic chokepoint—its security is a shared responsibility. Treating it as merely “Europe’s problem” underestimates how deeply interconnected our global systems truly are.

—Racha Helwa is the director of the empowerME Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

What did we learn about the campaign against the Houthis?

The leaked Signal conversation reveals a reckless method of bombing that is immoral as well as irresponsible. It is political performance rather than war effort—one more keen on signaling than on meaningful action.

These attacks are an extension of the campaign initiated under the Biden administration but on a much larger scale. The messages show that the Trump administration is chasing headlines without any concern for the wider consequences of targeting the Houthis. The war is being waged at a distance, with no real concern for the devastation left behind. The lives of civilians are collateral damage, while the Houthis themselves are spared to a large extent.

More troublingly, the leaked messages indicate officials gloating over these attacks with emojis, even though there have been subsequent reports of high civilian casualties. These attacks are not meant to incapacitate the Houthis but to send a message to Iran and validate Trump’s criticisms of the Biden administration’s efforts to deter the Houthis. Meanwhile, Meanwhile, the most senior Houthi leaders continue to implement security measures to keep them safe from attacks, limiting their vulnerability to strikes even as lower-level leaders and members are killed.

This bombing campaign is no serious effort to undermine the Houthis, nor is it an articulation of a coherent Yemen policy. Instead, Yemen is being used as a battlefield in an even broader war against Iran with little regard for the millions of Yemeni citizens who call the country home.

—Osamah Al Rawhani is a nonresident senior fellow with the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

***

The published Signal chat offers a rare glimpse into how the Trump administration assesses the Houthis’ current threat level, as well as their military capabilities. Although the group remains a serious threat to Israel and international maritime traffic, the chat suggests that their threat trajectory is not rapidly accelerating. Officials including Central Intelligence Agency Director John Ratcliffe, Hegseth, and Joe Kent, Trump’s nominee to be director of the National Counterterrorism Center, all indicated that delaying the operation would not significantly alter the rebels’ strategic position. This suggests that the Houthis may be persistent, but they are not rapidly advancing.

The messages also underscore the Houthis’ continued success in shielding their senior leadership from detection. Ratcliffe’s comment that more time would be useful “to identify starting points for coverage on Houthi leadership” highlights the success of the group’s long-standing efforts to keep their leaders hidden, especially the group’s leader, Abdel Malik al-Houthi, who is rarely seen in public and frequently relocates to avoid being targeted. By keeping their senior leadership structure largely intact, the Houthis have maintained operational control even when faced with sustained external pressure.

Additionally, the chat contained comments stating that the Houthis’ arsenal of missiles and drones are effective enough to evade European naval defenses. This shows that Iranian efforts to transform the group from a small militant faction to a capable military force, which have been limited compared to what Tehran has provided other groups like Hezbollah, have been largely successful. That revelation raises concerns that additional assistance from Iran, as well as support from other US adversaries such as Russia and China, could act as a force multiplier and accelerate the Houthis’ long-term transition into a fully modernized military force capable of exerting significant influence over regional security.

—Emily Milliken is the associate director of media and communications for the N7 Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 21, 2025

Trump’s Middle East strategy is all about striking an Iran deal. Gaza could get in the way.

New Atlanticist By Alan Pino

Recent US actions in Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon fit together in supporting the central objective of a deal with Iran.

Sat, Mar 15, 2025

Experts react: Trump just ordered major strikes against the Houthis. What does this mean for Yemen, Iran, and beyond?

New Atlanticist By

Atlantic Council experts break down the biggest military campaign of the second Trump administration.

Tue, Mar 18, 2025

Beyond the Houthis: The US needs a comprehensive Yemen policy

New Atlanticist By Osamah Al Rawhani

Recent air strikes mark a new chapter in the US approach toward the Houthis. But to be successful in reducing threats in the region, Washington will need policies that address Yemen as a whole.

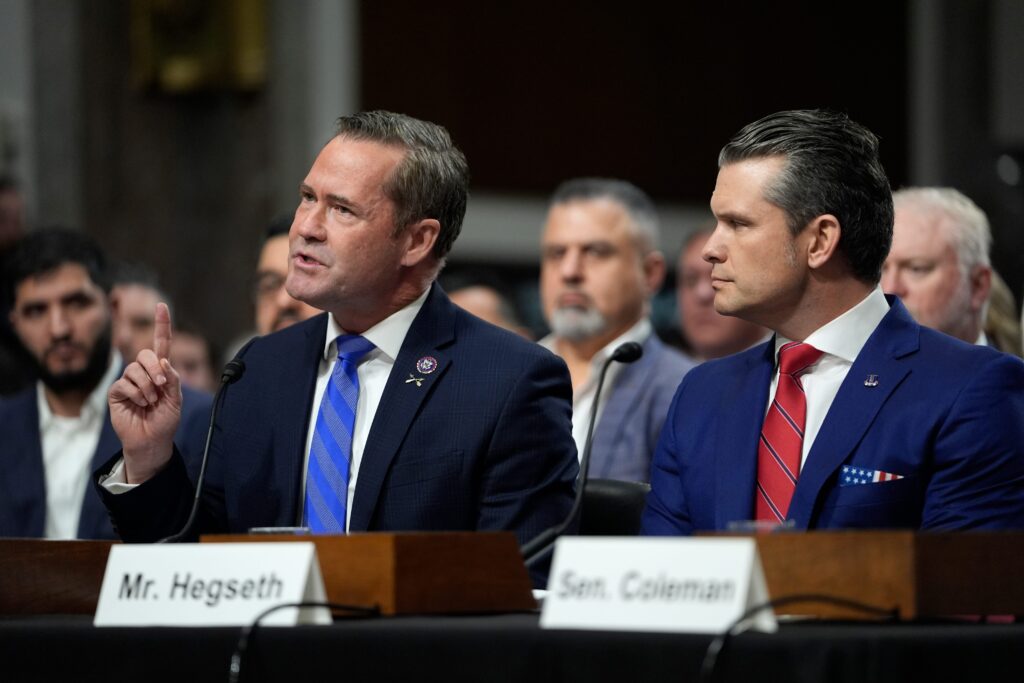

Image: Incoming National Security Advisor Michael Waltz (L) delivers remarks during a Senate Armed Services committee hearing on the expected nomination of Pete Hegseth to be Secretary of Defense on Tuesday, Jan. 14, 2025 in Washington, D.C.